Migrant Crisis: A Brief History

“Last year, 22 million refugees fled their home countries. On average, they will have to wait 10 years to go home” — David Miliband, CEO of the International Rescue Committee.

The movement of displaced people is not a refugee crisis, it is a humanitarian crisis.

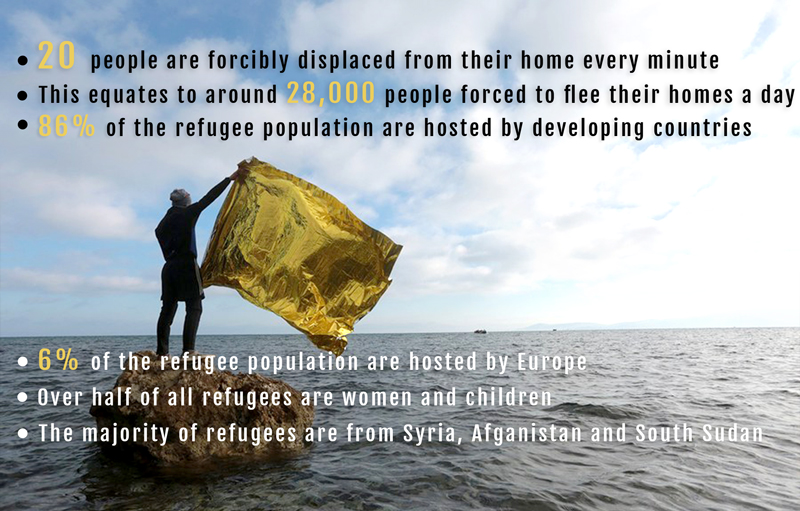

Currently, more than 65 million people across the globe are displaced from their homes as a result of conflict and persecution, the most ever in recorded history. That equates to one person in every 113 people on the planet being forced to leave home. Half of those people are children. Many of these people are on the move now, seeking safety elsewhere in the world in greater numbers even than during the years following World War II.

The scope and scale of the issue commonly referred to in the media as the “migrant crisis” is so large that it’s complicated to grasp a realistic picture of what it means.

Here's our attempt at summarising the issue in a few short paragraphs.

The European migrant crisis refers to the period beginning in 2015 when refugees, primarily Syrians fleeing a brutal civil war, began heading through Turkey and Greece into mainland Europe in large numbers. Prior to 2015, many displaced people from Syria were living in neighbouring countries including Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan. Conditions in the refugee camps were deteriorating and the numbers continued to grow. Eventually, refugees began to cross the Mediterranean and Aegean seas, heading to Europe in unprecedented numbers. In 2015, over one million people arrived by boat in Europe, the majority from Syria, but also from Afghanistan, Iraq, Kosovo and Albania.

Since 2012, the Syrian conflict has continued to produce the highest numbers of migrants — half of Syria’s 22 million people population are currently displaced and around 5 million of those people have fled the country.

For the last few years, conflict and persecution have been driving people from their homes in an array of countries and regions apart from Syria, including Gaza, Pakistan, Iran and the Ukraine, as well as Eritrea, Nigeria and Sudan in North Africa.

The massive influx of people to Europe created tensions in the EU as the union considered ways to receive, process and potentially settle the asylum seekers. The vast majority of migrants arrived in Greece and Italy with the intention of moving further into mainland Europe. Over 800,000 people continued onto Germany, invited by chancellor Angela Merkel who announced a now historic “no limits on the number of asylum seekers” and vowed to “do what is necessary” to help refugees.

During the two-year influx, many other European countries closed their borders, as housing and resources for the large numbers of migrants were in question.

In March 2016, as asylum seekers continued to arrive, the EU signed a deal with Turkey attempting to control the flow of migrants crossing from Turkey to Greece. The EU-Turkey agreement, otherwise known as the “refugee deal” is a fragile arrangement that has stemmed the flow of people but has not prevented arrivals from continuing. In Greece, a range of support centres have been created to help and host over 60,000 asylum seekers who remain there, no longer able to cross borders and continue their journey.

While the spotlight is on the evolution of the situation in Europe, the fact remains that the West has not shouldered the majority of the refugee population seeking safety.

The UN identifies the present number of refugees and asylum seekers at 22 million.

Of those 22 million, Europe currently hosts 6%, the majority in Germany, while over 80% are in camps and informal settlements in the world’s developing countries. Turkey hosts 2.9 million refugees, the highest number in the world followed by Pakisatan with 1.4 million. The top 10 refugee hosting countries globally are developing countries that account for a miniscule 0.25% of the world economy.

In 2017, further unrest and conflict in North Africa has turned the focus to Italy where 60,000 refugees have already arrived this year, primarily from Libya. More than 2,000 people have died in 2017 attempting the crossing.

Howling Eagle is a project motivated to highlight the array of constructive humanitarian solutions that have been devised and adopted to support millions of these people whose lives remain in a state of limbo.

Emma Pearce

Further Reading:

Europe’s Migrant Crisis, Council on Foreign Relations

The Migrant Crisis: No End in Sight, New York Times

Refugee Crisis on Leros: Report From the Ground, The Huffington Post

Zaatari’s Children: Life in a Refugee Camp, The Guardian

Migration Figures at a Glance, UNHCR

News Focus: Migrants and Refugees, United Nations